Book Review by John Rogers

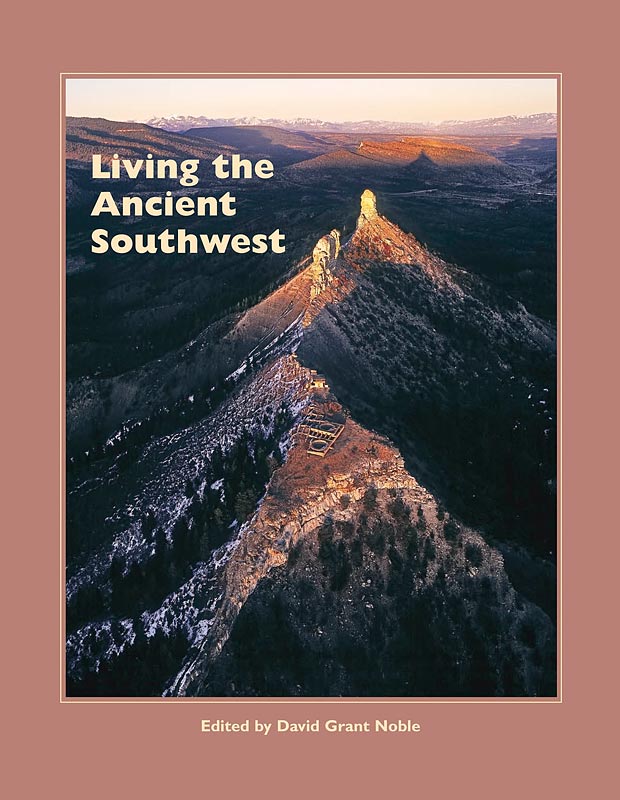

Living the Ancient Southwest, ed. David Grant Noble

A School for Advanced Research Popular Archeology Book

SAR Press, Santa Fe, 2014

Available from SAR Press (www.sarpress.org) and at many National Park Service bookstores

Living the Ancient Southwest is a collection of eighteen essays by scholars and specialists affiliated with the School for Advanced Research intended to share knowledge with a broad, interested, non-specialist audience. The goal is to introduce the general reader to the Southwest’s archeological and anthropological heritage.

As the title suggests, the focus of the book is on practical living matters that faced Native Americans in the region, with an emphasis on how indigenous peoples met the challenge of living in the desert. Several chapters are also devoted to their artistic creativity, describing and analyzing such cultural expressions as architecture, ceramics, rock art, and farming strategies. Native American insights into history, places, religion and philosophy are also explored.

The geographical areas covered in the volume include the Fremont cultural area (central Nevada), Ancestral Pueblo (the Colorado Plateau, San Juan Basin, and Grand Canyon), and the Hohokam cultural area (Tonto Basin and Sonoran Desert).

Chapter titles early in the book reflect its concerns: “Making a Living in the Desert Southwest;” “Pueblo Farmers of the Chacoan World;” and “The Environment of the Ancient Mesa Verdeans.” Of particular interest to New Mexicans are essays about cavate pueblos in Frijoles Canyon, ancient trail systems on the Pajarito Plateau, the architecture of Chaco Canyon, Zuni religion and philosophy, Mimbres pottery, and Hopi accounts about the origins of Chaco. Other essays address ancient violence in the Mesa Verde region, Canyon de Chelly rock art and its relationship to the rock art of Ancestral Puebloans, and Fremont and Hohokam cultures.

A synopsis of one essay illustrate the type of content a reader may expect. Alexa Roberts writes about the area around an Ancestral Puebloan site, Wupatki Pueblo, located in north-central Arizona between Flagstaff and Tuba City. “The Wupatki Navajos: An Historical Sketch” recounts the story of Peshlakai Etsidi, one of the first Navajo to live in the Wupatki area following the return of Navajos in 1868 from Bosque Redondo at Fort Sumner. Simultaneously, a protestant missionary, the Reverend William R. Johnston and his family arrived in the area, and a friendship was struck up between the two men. Local Anglo ranchers and farmers, coveting the fertile land and water resources near Wupatki and the Little Colorado River, imposed an arbitrary tax on sheep, threatened violence when Etsidi and others were unable to pay it, and forced many Navajo to flee the region. Reverend Johnston decided to advocate on behalf of the tribe, accompanying Etsidi and two other headmen to Washington, D.C., where they presented their case to President Theodore Roosevelt. Johnston’s young son, Philip, who had grown up with the Navajo language and was fluent, acted as the interpreter for the meeting, which was successful: Roosevelt “instituted an immediate program of reservation boundary extension and Indian allotments in the western territory,” stabilizing the Wupatki Navajos’ grazing lands. The looting of archeological sites also prompted Roosevelt to send the National Park Service to the area to oversee cultural assets. By the time Peshlakai Etsidi died in 1939, Wupatki National Monument had grown from approximately 2,200 acres to nearly 35,000 acres, with Philip Johnston and his sister, Bernice, continuing to advocate for the preservation of historical and cultural assets in the area. In 1942, forty years after acting as an interpreter for Etsidi’s meeting with Teddy Roosevelt, Philip recognized the potential of the Navajo language to aid the American effort in the Pacific during World War II, and organized the Navajo Code Talkers. “The Wupatki Navajos fought in the war as well, and many young men enlisted in the army to serve the nation, less than eighty years after the US Army had imprisoned their grandparents at Fort Sumner.”

Living the Ancient Southwest is filled with exciting, insightful essays about our region’s first inhabitants and their strategies for adapting to the environment of our area. Maps, illustrations, and color plates clarify and augment the prose. Taken as a whole, the book is an excellent introduction to the early history and culture of the land that we share today.